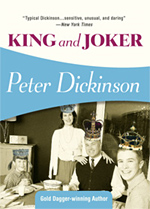

By some measurements, Peter Dickinson’s King and Joker was one of the first adult SF novels I ever read. By others, you could say it was one of the first adult mysteries, though I found it on the SF shelf. It’s probably not something anyone else would see as a great influential work, but it’s hardly possible to find anything that’s influenced me more. It’s a mystery set in an alternate history. It’s not a story about the alternate history, though the background is well worked out and the revelations are well fitted in to the story. I’m reluctant to say it isn’t SF, because the experience of reading first King and Joker and then The Dispossessed on the same afternoon is what made me fall in love with the possibilities and scope of a brave new genre that had such wonders in it.

I’d actually read several SF books before—Poul Anderson’s Guardians of Time, and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day, Clarke’s Time and the Stars, The Penguin Best SF collection, others. But I’d never made the connection that these all fitted into one category—I’d read some science fiction, but without being aware of it. Awareness of the genre came from King and Joker, The Dispossessed and the fact they both came from the shelves in the adult library marked “Science Fiction”.

If I were to read King and Joker now for the first time I’m not sure how I’d define it, and I’m not sure how I’d rate it. I’ve been reading it every year or so since I was twelve, and my first overwhelmed read on the riverbank inevitably colours all subsequent readings. King and Joker is a grown up mystery—it’s full of sex and sexual motivations in the exact way that Agatha Christie isn’t. But it was very easy for me to read. It’s largely from the point of view of a fourteen year old girl, a princess in Buckingham Palace in a world where the succession has gone a little differently because Edward VII’s eldest son survived. It’s a story about having a public face and a private face, about how secrets can be poisonous, and about growing up. The alternate history is essential to the story, which has to be about a different royal family, and science is important, in terms of genetics and hemophilia and the machine that keeps Durdy alive. There’s definitely a murder and a murderer and a mystery. All the same, first and foremost this is a story about people.

Peter Dickinson is a wonderful writer, and thinking about it now, after having read all his books for children and for adults, fantastical and mundane, his real theme is how what we remember shapes our worlds.

King and Joker was published in 1976 and was set at about the same time. The point of divergence (“Jonbar point”) between their world and ours was the death, in our world, of Queen Victoria’s grandson Prince Arthur Edward in 1892. In their world he became King Victor I, in ours his brother became King George VI. Dickinson considers that it wouldn’t have made very much difference to the wider events of the world whether Britain has a queen with corgis or a king with bulldogs. There’s still WWII, and the end of the Empire, and in the mid-seventies Britain’s still in the grip of a recession and everyone’s cutting back, and the tabloid papers are fascinated by the details of royal life. The king has been trained as a doctor but the unions won’t let him treat anyone. The book begins with the royal family at breakfast going through a list of suggested money-saving ideas and rejecting one that suggests they should no longer keep a supply of sealing wax in all the guest bedrooms.

What Dickinson’s really doing is taking his royal family, who because of what they are must lead lives that are both public and private, open and hidden, and using them to talk about the way secrets fester. There’s a lot of the scenery of the typical cosy mystery—the old nanny who has known generations of children, pots of tea and crumpets by the fire. But the old nanny’s true love that she gave up to stay with her babies was a woman, and the king and queen who wave so nicely have a third person in their marriage. There are layers here, and a lot more depth than you might expect. Dickinson takes two people, the old dying Durdy, nanny to half the crowned heads of Europe, and Princess Louise, the girl on the cusp of adult understanding. Through them he evokes a whole world. Durdy’s old enough to have met Queen Victoria, and Louise is going to live into the twenty-first century. They’re facing in different directions, and this is the meeting point.

I always read this book in one session—it’s not very long, and I never want to put it down.

There’s a much less successful sequel, Skeleton in Waiting.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.